Making an Impact on Persistence, Retention and the First-Year Experience

Peer mentorship has been increasingly embraced as a high-impact practice in higher education (Collier, 2017). Motivated by research validating the role of mentorship in student persistence, senior leaders are expanding their tactics to ensure first-time college students return the following academic year (AY). This also applies to second-year students in the 2021-2022 AY that may be unfamiliar with in-person classes and campus resources due to online and hybrid learning throughout 2020.

Now in its seventh year of industry-leading, large-scale mentorship programs with more than 100 partnering institutions, Mentor Collective has released a new white paper exploring the connections between peer mentoring, intrapair engagement, and term-to-term persistence for the 2020-21 AY. This in-depth analysis spanning six institutions and more than 17,000 students was conducted by Mentor Collective’s Research Lead, Jenna Harmon, Ph.D., and Boldr Impact Data Scientist Sandy Lauguico and yielded important findings on:- Fall-to-spring semester persistence rates for mentored students compared to their non-mentored peers

- The impact of mentorship on a student’s likelihood to persist from term to term

- How important mentor-mentee engagement is to a student’s likelihood to persist.

We recently sat down with Dr. Harmon to discuss the importance of this research, why retention matters from a student (and university) perspective, and how research-based mentorship programs contribute to achieving student persistence.

We recently sat down with Dr. Harmon to discuss the importance of this research, why retention matters from a student (and university) perspective, and how research-based mentorship programs contribute to achieving student persistence.

There’s been a lot of research surrounding mentorship and its impact on the student experience. What questions do you feel this study answers? What other research does it build upon?

There’s an ongoing need for quantitative studies of the efficacy of mentorship in addressing a range of issues, including that of student persistence. While this was an observational and not an experimental study, the results we found are impressive and make contributions to the larger field of mentorship studies, specifically in better understanding how mentorship works and under what circumstances. As you can see in the document itself, we have over five pages of citations for a 13-page paper, so this study is deeply indebted to the work of many scholars across many disciplines, especially in psychology and education. This is because mentorship research is dispersed across a lot of different fields and, by extension, academic journals. One of the things I’m passionate about as a researcher at Mentor Collective is synthesizing these publications together and bringing the information they carry out from behind the paywalls of journals. Practitioners don’t necessarily have the time and resources to be hunting down these findings, so I feel strongly that this is a role that I can play not just for Mentor Collective, but for our larger Collective.

Is there a need to continue validating the connection between mentorship and persistence (and retention)?

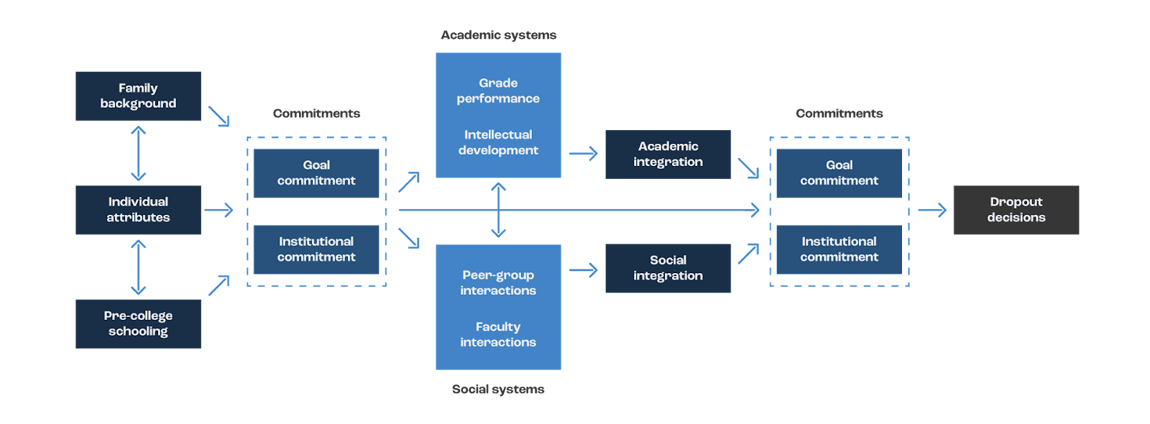

It’s less about needing to validate the connection, and more about pinpointing where these two complex phenomena intersect. As education researchers know well, student persistence is a multifaceted issue that encompases many factors, including gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, and geography. Mentorship is also multifaceted, in that there are, in fact, many definitions for it in the academic literature. Sometimes it’s defined as a relationship, sometimes it’s a process, sometimes it’s a form of support. What I think Vincent Tinto’s work offers, and why we leaned on his theoretical framework in this particular study, is at least one clear point of intersection between mentorship and persistence in the form of social integration.

Tinto’s Student Integration Model

How do Mentor Collective programs contribute to the conditions necessary for students to persist?

As I said before, student persistence incorporates many different things. What Mentor Collective helps schools provide to students is a more personalized resource in the form of a mentor. I think many administrators want to believe that mentorship is happening at sufficient levels in their classrooms, but sit down with any given faculty member and you’re likely to hear how busy and stressed out they are, between the need to conduct and publish original research, prep and teach courses, grade those courses, and then fulfill their university service requirements. This is to say nothing of the state of affairs for contingent faculty, which is far, far worse. So not only do faculty not have the time or professional incentives to provide mentorship to that volume of students, but research has actually shown that students aren’t necessarily inclined to confide in their professors in that way, due to the inherent power differential in the relationship. This isn’t to say that those relationships never occur, but they’re nowhere near as frequent as we’d all like to believe, especially for historically underserved students. By providing students with a peer mentor, that power differential is greatly reduced, and students are much more likely to open up and share their struggles, which in turn makes it possible for mentors to direct resources to students who may be struggling.

You mentioned many administrators believe that mentorship is happening at sufficient levels on their campuses already. Why do you think researched-based mentorship programs should be at the forefront of consideration?

My thinking on this has been deeply influenced by Jean Rhodes’s work, especially her recent book Older and Wiser. Mentorship as a practice seems profoundly human, which is why I think so many different kinds of organizations and institutions have gravitated towards it as something to incorporate into how they operate. But as Jean points out, there’s often a lot more positive intention behind these efforts than science. There is enormous potential for mentorship as a student success intervention, but it has to be implemented in accordance with established best practices to be effective. What I think sets Mentor Collective apart is that it’s a full support system of professionals with experience in education and technology. That kind of “wraparound” support reduces the number of staff hours needed to run and manage a successful mentorship program, allowing those who have already been running programs to spend more time focusing on their students rather than on complicated logistics. Mentor Collective also actively supports mentors with custom training and conversation guides rooted in pedagogical standards to help them navigate situations they may encounter with their mentee.

What happens next now that you have this information?

More research! Specifically, my co-author and I are interested in pursuing year-over-year retention patterns from Fall 2020 to Fall 2021, once the latter data becomes available. We’re also interested in connecting these enrollment data sets to our assessment data on sense of belonging and self-efficacy. We’ll also be keeping an eye on data regarding interaction modality to see if mentor/mentee interactions remain primarily virtual or if in-person interaction increases, and compare it against other metrics such as frequency of conversations and sense of belonging.

Mentor Collective designs effective mentorship experiences rooted in science. Contact us to learn more about how it can impact student persistence and retention at your institution.